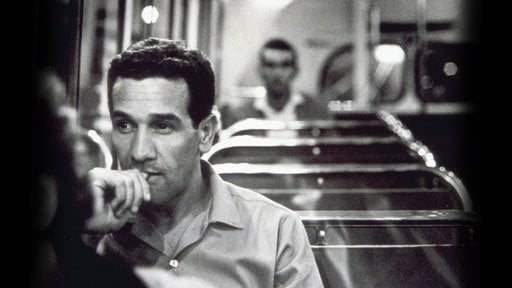

CHARLIE’S LESSONS AND LEGACY

The Dr Charles Perkins Oration – University of Sydney, 12 November 2020

Werte – Hello, my name is Pat Turner.

I am honoured to deliver this year’s Charles Perkins Oration.

To stand where Charlie stood, at the University of Sydney, where he was the first Aboriginal man to graduate from a university in Australia.

I acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the traditional owners and custodians of this land and pay my respects to their Elders past and present.

I also acknowledge Charlie’s family.

I extend my warmest regards to his daughters, Hetti and Rachel, and to his son, Adam.

Hetti, Rachel and Adam are watching tonight from Charlie’s birth and resting place, at the Bungalow in Alice Springs.

Their mother, and Charlie’s wife, Aunty Eileen, is with me tonight. I thank Aunty Eileen for her support over many years.

Charlie was my uncle, but we didn’t talk about each other like that, as niece and uncle. We were just family.

I acknowledge Chancellor Belinda Hutchinson AC, Vice Chancellor and Principal Dr Michael Spence AC, Deputy Vice Chancellor Professor Lisa Jackson-Pulver AM, The Perkins Family, the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council and the combination of the University of Sydney and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, who have worked together to bring this event to fruition.

Charlie’s influence

Charlie is as much of an inspiration to me now, as he was when I was a kid.

I remember when he would come home to Alice Springs and tell stories of the fight for the civil rights of Aboriginal people.

Charlie would be under a tree, with a group gathered around, and talking loudly about his latest battles.

A child of 12, I would be hanging back a bit, but close enough to take in Charlie’s every word, to take in as much as I could.

I was in awe and I was proud.

In awe as Charlie was taking on the country, taking on the fight for equality of our people in a way and on a scale that had not been seen before.

And proud that by being part of Charlie’s family, I was already a part of that story for change.

In his stories, Charlie would set out what he saw as the difficulties Aboriginal people faced today, and tomorrow.

He set out those difficulties with the courage and fire to imagine a better world despite them.

And it was under that tree that he talked through the cultural, legal, and moral changes that needed to take place in Australia, and the courage required, in order for us to create that better world.

It is Charlie’s courage, and the fire that he had in his belly that has guided many of the decisions in my life and career and continues to light much of my path today.

To the nation, Charlie is remembered as a man who dedicated his life to achieving justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, a renowned activist and fearless spokesperson.

To me, Charlie will always be the man who came home and talked under the tree.

Holding a mirror to our nation

Whilst Charlie’s achievements are too numerous to recount in detail tonight, his life provides many lessons for us trying to follow in his footsteps.

An early lesson that stands out is the need to mobilise the media. To tell stories of hope to our own people and to call out the nation for its appalling treatment of his people.

Following his death in October 2000, I delivered his eulogy to an overflowing Sydney Town Hall.

In that tribute, I spoke from my heart, and my head, when I observed that Charlie held a mirror in front of this country and exposed the discrimination and racism our people endured.

Charlie knew that for Australia to front up to the plight of Aboriginal people they had to be shown what was right there in front of them.

This desire led to both the formation of the Student Action for Aborigines group and the decision to organise a bus tour of western New South Wales towns.

His role in instigating and undertaking the Freedom Ride in 1965 changed mindsets in mainstream Australia.

The Freedom Ride showed the nation the poor state of Aboriginal health, education, and housing.

But through the media, Charlie and his comrades also highlighted the discriminatory barriers which existed between Aboriginal and white residents.

Through the effective use of television, Charlie managed to get a national audience to face up to Australia’s racism, to turn the mirror on our nation.

Challenging the consciousness of Australia through the Freedom Ride made Charlie the early spokesperson for our people and to many non-Indigenous Australians, a mischief maker.

Not that he was too fussed with what white Australia thought of him, as Charlie was also working to mobilise our own people.

He wanted Aboriginal people, his people, to see that we deserved more, should demand more, and could be more.

As Charlie said,

“The Freedom Ride was not for the white people, but to tell Aboriginal people that they didn’t have to be second class.

I wanted to say: ‘don’t cop shit when you don’t have to’.

And I think they listened.”

Charlie would reflect to me later how important the media was in changing our nation’s treatment of Aboriginal people.

The trick, he would say, was to make sure you were in, and challenging, today’s news, but to do it in a way that meant you were not tomorrow’s fish and chips wrapping.

I am not sure how Charlie would describe today’s digital news and the fast pace of the news cycle, but his lesson of effectively using the media to call out the inequality faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is a lesson I have not forgotten.

Knowing the systems, you are seeking to change

Perhaps Charlie’s greatest lesson for us though, is the need to know, understand and be part of the systems you want to challenge and change.

If we look back at each of the major developments in Indigenous Affairs policy since the 1960s – Charlie was always there. And he was there because he knew how to change and influence policy.

Charlie understood that achieving equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples required more than governments providing funding for health, housing, essential services, education, and employment of our people — important as this is.

He understood that a solution was also required to the structural problem caused by our people being excluded from the colonial institutions established to govern Australia.

Charlie knew too that it was vital that Aboriginal people had to be fully involved in running Aboriginal Affairs.

To do so, and to do so well, Charlie first set out to study and learn about the systems he wanted to change.

At university, Charlie chose to study political science, because, in his words, he wanted “to investigate the institutions of government: how they operate, who operates them and how you can run an Aboriginal organisation as a pressure group.”

Charlie installed this lesson in me at an early age. I had caught a train from Alice Springs with Nanna Perkins to watch Charlie graduate in 1966.

As I stood here, on the grounds of the University of Sydney, watching Charlie, I knew I had to pursue my own education for the same purpose.

Charlie saw the potential for national change, by working within the administrative system to influence policies that affected Aboriginal people.

Charlie knew that to truly challenge the deeply ingrained ways of bureaucracy, and to make the systems that were designed and intended for our peoples’ benefit to truly work for our benefit, he had to do so from inside government.

Charlie was not just an advocate who gave speeches, wrote articles, and carried flags at rallies. He chose to engage with governments directly – to step inside the tent.

In doing so, he became the first Aboriginal person to head a government department.

Charlie saw being in government, inside the tent, as a means to direct funding directly to our communities and to influence at the highest levels of decision making. And he encouraged me to pursue that same objective.

Like Charlie, I too have spent a great deal of my career inside government.

Drawing on his lessons, I used much of this time to observe, campaign, take opportunities for our people where I could and to learn how decisions were made, and how to secure political support for programs for Aboriginal people.

Taking real control

While Charlie believed in the importance of change from within, he also teaches us the lesson of Aboriginal control.

True Aboriginal control, where we are exercising our political agency as Aboriginal people over our own affairs, designing, and delivering our own programs, without the constraints of government.

During Charlie’s life, he oversaw the establishment of many Aboriginal controlled and run organisations designed to deliver the services we needed, on our own terms.

It is here where I am now dedicating my time and where I see the most potential for our peoples.

Like Charlie, I realised that there was a limit to what could be achieved for our people inside government.

In government, we are always working in a system that is not ours; one that is designed to serve a purpose that is beyond Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander interests alone.

Aboriginal community-control is an act of self-determination for our peoples. It is how we exercise greater political agency within the present policy landscape.

Currently, and in my view, there is no other way of delivering and governing services, or providing us with a say in policy and programs, that guarantees Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander empowerment and protects our identity and culture for the long term.

There is strong evidence that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled services are better for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, achieve better results and help make sure we get the support we need.

Community-controlled organisations employ more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than mainstream organisations and result in communities taking more responsibility for services.

Through their involvement in policy and political advocacy, our organisations also provide a voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Without them, the accountability of governments would be far weaker.

Whilst I believe that our community-controlled organisations are the best form of political agency for our people, a relationship with government, and a government that is responsive to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, is still required.

This is a recognition that we have a shared future – Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, together – and that the two sides must come together to deliver lasting equality and recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The lessons I learnt from being inside government and the lessons and importance of Aboriginal community-control – Charlie’s lessons – are being brought to bear in a new partnership between a Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community-Controlled Peak Organisations and all Australian governments.

The Coalition of Peaks are made up of nearly fifty-five national and state/territory community controlled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations.

We formed as an act of self-determination and came together to be formal partners with all Australian Governments on Closing the Gap – a policy about achieving equality for our people.

All of our leaders, who have been sitting at the negotiating table with governments, have either been elected to the boards of our organisations by members of the communities they serve or have been appointed by Boards as CEOs of their organisations.

We have worked with our communities for decades on matters that are important to our people in areas like health, early childhood, education, land rights and legal services.

Every member organisation has its own extensive network made up of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations that they regularly engage with to represent their interests.

The Coalition of Peaks have brought our own political agency to the table, and through a negotiated formal partnership arrangement with governments, have agreed to a new National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

It is the first time that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peaks have come together in this way.

And it is the first time an intergovernmental National Agreement designed to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been developed and negotiated between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives.

The National Agreement commits the country to a new way of working between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to address the inequities that our people continue to face.

It is a new way of working that is based on negotiation and shared decision-making between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

But it is early days, and the months and years ahead will be testing times.

For the Coalition of Peaks, we need to continually strengthen our own governance and stay connected with our communities at the same time working to keep ahead of the game, to stay in front of Australian governments with their many resources.

Governments will also need to demonstrate that their institutions and bureaucracy can embrace the change and reform to meet the challenge and commitments set out in the National Agreement.

Lasting change can only come when it is embedded in the culture of organisations and traditionally Australian governments are also slow to adapt.

The matter of much needed, significant funding for services and supports for our peoples, remains an issue that is yet to be fully addressed by governments.

What is different now though, is that we have a formal seat at the table with governments.

We believe ultimately, a partnership between community-controlled organisations and governments will achieve better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – where we are both inside and outside of the tent.

And even if the National Agreement fulfils its promise, the picture of reform is far from complete.

A First Nations Voice to the Commonwealth Parliament, to monitor and advise on making laws with respect to our people is still missing from the political and policy landscape.

So too is national Truth Telling and Treaties.

Standing up for what is right

This new partnership with governments, and the work of the Coalition of Peaks, has not come without its criticism, including from our own people.

So, the last lesson from Charlie’s life I want to share with you today, is to stand up for what you believe is right, and to seize the opportunities you have.

It is probably the hardest lesson to practice from Charlie’s life.

From an early age, Charlie was prepared to stand up for what he believed in, for what he thought was right.

Over the course of his life, he never backed down.

In never backing down, Charlie’s life led to great gains for our peoples.

In speaking out, his life was not just for himself and his family, but for his people and ultimately for Australia.

Charlie’s approach to life must continue to inspire us all to more unified and purposeful action.

Action where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are collectively taking back control of our own affairs.

As we reflect on the lessons and legacy of Charlie’s life, of his courage, the fire in his belly and the fire he lit in so many of us, I leave you with his own words:

I am here today, gone tomorrow, and I’ve only just played a small role like other Aboriginal leaders do, but we’re only passing, you know, ships in the night really.

And where the answer lies, is with the mass of Aboriginal people, not with the individuals.